Major Gordon Dailley traveled 500 kilometers in a single day in his Canadian Army jeep in the spring of 1945, from the Netherlands to Berlin.

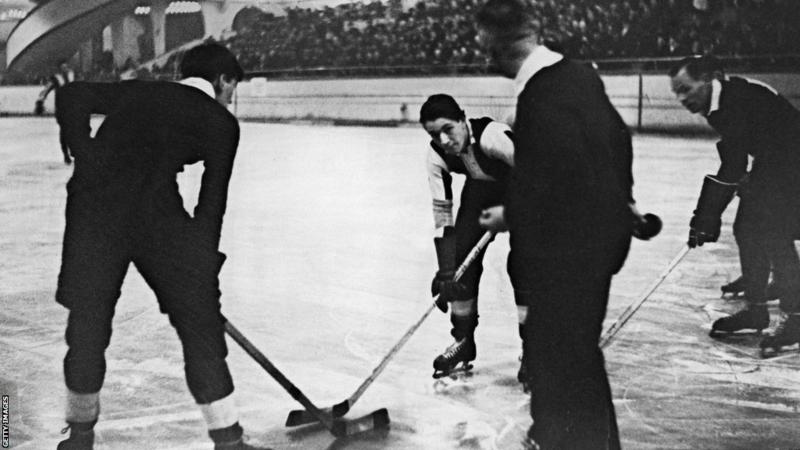

Nine years previously, when he had assisted Great Britain in winning the gold medal in ice hockey at the 1936 Winter Olympics, he had made his sole previous trip to Germany. On the journey, he had met Adolf Hitler. He didn’t do it this time.

Three days after the Fuhrer’s suicide and as World War Two was nearing to a close, Dailley landed in Berlin. He ran into Ian Gordon there.

Gordon covered both the collapse of the city and the victory of the Allies as a war correspondent. However, he had written about ice hockey and Dailley the player in a past peaceful existence.

Gordon climbed into the jeep, and the two of them drove around the destroyed city of Berlin. They soon came to the remnants of the Reich Chancellery, the center of Nazi authority, and discovered several abandoned jerry cans in the garden.

The two concluded that they were likely involved in the cremation of Hitler. Nobody could be heard saying otherwise in the confusion. Dailley deemed them suitable as gifts.

Later, they passed a line of people waiting to get soup from Allied troops. One scruffy man drew their attention. It was Rudi Ball, a person they had last seen in very different circumstances less than ten years prior.

Dailley had competed against Ball, the Jewish star of Germany’s ice hockey squad, at the 1936 Olympics. Gordon and Dailley were in disbelief. Ball’s wartime survival is a mystery. How had he evaded the atrocities of Hitler?

Approximately 78 years later, trying to get the answer has not been simple.

Many unanswered questions have given rise to even more pertinent ones.